故都的秋

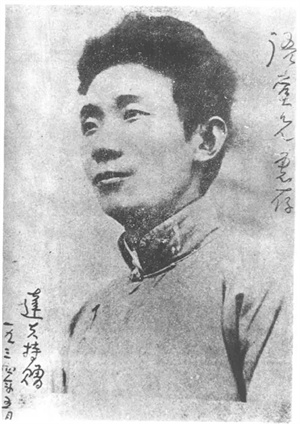

◎ 郁达夫

秋天,无论在什么地方的秋天,总是好的 〔1〕 ;可是啊,北国的秋,却特别地来得清,来得静,来得悲凉。我的不远千里,要从杭州赶上青岛 〔2〕 ,更要从青岛赶上北平来的理由,也不过想饱尝一尝这“秋”,这故都的秋味。

江南,秋当然也是有的;但草木凋得慢,空气来得润,天的颜色显得谈,并且又时常多雨而少风;一个人夹在苏州上海杭州,或厦门香港广州的市民中间,浑浑沌沌地过去,只能感到一点点清凉,秋的味,秋的色,秋的意境与姿态,总看不饱,尝不透,赏玩不到十足 〔3〕 。秋并不是名花,也并不是美酒,那一种半开,半醉的状态,在领略秋的过程上,是不合适的。

不逢北国之秋,已将近十余年了。在南方每年到了秋天,总要想起陶然亭的芦花,钓鱼台的柳影,西山的虫唱,玉泉的夜月,潭柘寺的钟声 〔4〕 。在北平即使不出门去罢,就是在皇城人海之中,租人家一椽破屋来住着,早晨起来,泡一碗浓茶,向院子一坐,你也能看得到很高很高的碧绿的天色,听得到青天下驯鸽的飞声。从槐树叶底,朝东细数着一丝一丝漏下来的日光,或在破壁腰中,静对着像喇叭似的牵牛花(朝荣)的蓝朵,自然而然地也能够感觉到十分的秋意。说到了牵牛花,我以为以蓝色或白色者为佳,紫黑色次之,淡红色最下。最好,还要在牵牛花底教长着几根疏疏落落的尖细且长的秋草,使作陪衬。

北国的槐树,也是一种能使人联想起秋来的点缀。像花而又不是花的那一种落蕊,早晨起来,会铺得满地。脚踏上去,声音也没有,气味也没有,只能感出一点点极微细极柔软的触觉。扫街的在树影下一阵扫后,灰土上留下来的一条条扫帚的丝纹,看起来既觉得细腻,又觉得清闲 〔5〕 ,潜意识下并且还觉得有点儿落寞,古人所说的梧桐一叶而天下知秋的遥想,大约也就在这些深沉的地方。

秋蝉的衰弱的残声,更是北国的特产;因为北平处处全长着树,屋子又低,所以无论在什么地方,都听得见它们的啼唱。在南方是非要上郊外或山上去才听得到的。这秋蝉的嘶叫,在北平可和蟋蟀耗子一样,简直像是家家户户都养在家里的家虫 〔6〕 。

还有秋雨哩,北方的秋雨,也似乎比南方的下得奇,下得有味,下得更像样 〔7〕 。

在灰沉沉的天底下,忽而来一阵凉风,便息列索落地下起雨来了。一层雨过,云渐渐地卷向了西去,天又青了,太阳又露出脸来了;著着很厚的青布单衣或夹袄的都市闲人,咬着烟管,在雨后的斜桥影里,上桥头树底下去一立,遇见熟人,便会用了缓慢悠闲的声调,微叹 〔8〕 着互答着的说:

“唉,天可真凉了——”

“可不是么?一层秋雨一层凉了!”

北方的果树,到秋来,也是一种奇景。第一是枣子树;屋角,墙头,茅房边上,灶房门口,它都会一株株地长大起来。像橄榄又像鸽蛋似的这枣子颗儿,在小椭圆形的细叶中间,显出淡绿微黄的颜色的时候,正是秋的全盛时期;等枣树叶落,枣子红完,西北风就要起来了 〔9〕 ,北方便是尘沙灰土的世界,只有这枣子、柿子、葡萄,成熟到八九分的七八月之交,是北国的清秋的佳日,是一年之中最好也没有的golden days。

有些批评家说,中国的文人学士,尤其是诗人,都带着很浓重的颓废色彩,所以中国的诗文里,颂赞秋的文字特别的多。但外国的诗人,又何尝不然?我虽则外国诗文念得不多,也不想开出账来,做一篇秋的诗歌散文钞,但你若去一翻英德法意等诗人的集子,或各国的诗文的anthology来,总能够看到许多关于秋的歌颂与悲啼。各著名的大诗人的长篇田园诗或四季诗里,也总以关于秋的部分,写得最出色而最有味。足见有感觉的动物,有情趣的人类,对于秋,总是一样的能特别引起深沉,幽远,严厉,萧索的感触来的。不单是诗人,就是被关闭在牢狱里的囚犯,到了秋天,我想也一定会感到一种不能自已的深情 〔10〕 ;秋之于人,何尝有国别,更何尝有人种阶级的区别呢?不过在中国,文字里有一个“秋士” 〔11〕 的成语,读本里又有着很普通的欧阳子的秋声 〔12〕 与苏东坡的《赤壁赋》 〔13〕 等,就觉得中国的文人,与秋的关系特别深了。可是这秋的深味,尤其是中国的秋的深味,非要在北方,才感受得到底。

南国之秋,当然是也有它的特异的地方的,比如廿四桥的明月,钱塘江的秋潮,普陀山的凉雾,荔枝湾的残荷等等,可是色彩不浓,回味不永。比起北国的秋来,正像是黄酒之与白干,稀饭之与馍馍,鲈鱼之与大蟹,黄犬之与骆驼。

秋天,这北国的秋天,若留得住的话,我愿把寿命的三分之二折去,换得一个三分之一的零头。

Autumn in Peiping

◎ Yu Dafu

Autumn, wherever it is, always has something to recommend itself. In North China, however, it is particularly limpid, serene and melancholy. To enjoy its atmosphere to the full in the onetime capital, I have, therefore, made light of travelling a long distance from Hangzhou to Qingdao, and thence to Peiping.

There is of course autumn in the South too, but over there plants wither slowly, the air is moist, the sky pallid, and it is more often rainy than windy. While muddling along all by myself among the urban dwellers of Suzhou, Shanghai, Xiamen, Hong Kong or Guangzhou, I feel nothing but a little chill in the air, without ever relishing to my heart’s content the flavour, colour, mood and style of the season. Unlike famous flowers which are most attractive when half opening, or good wine which is most tempting when one is half drunk, autumn, however, is best appreciated in its entirety.

It is more than a decade since I last saw autumn in the North. When I am in the South, the arrival of each autumn will put me in mind of Peiping’s Tao Ran Ting with its reed catkins, Diao Yu Tai with its shady willow trees, Western Hills with their chirping insects, Yu Quan Shan Mountain on a moonlight evening and Tan Zhe Si with its reverberating bell. Suppose you put up in a humble rented house inside the bustling imperial city, you can, on getting up at dawn, sit in your courtyard sipping a cup of strong tea, leisurely watch the high azure skies and listen to pigeons circling overhead. Turn eastward under locust trees to closely observe streaks of sunlight filtering through their foliage, or quietly watch the trumpet-shaped blue flowers of morning glories climbing half way up a dilapidated wall, and an intense feeling of autumn will of itself well up inside you. As to morning glories, I like their blue or white flowers best, dark purple ones second best, and pink ones third best. It will be most desirable to have them set off by some tall thin grass planted underneath here and there.

Locust trees in the North, as a decorative embellishment of nature, also associate us with autumn. On getting up early in the morning, you will find the ground strewn all over with flower-like pistils fallen from locust trees. Quiet and smelless, they feel tiny and soft underfoot. After a street cleaner has done the sweeping under the shade of the trees, you will discover countless lines left by his broom in the dust, which look so fine and quiet that somehow a feeling of forlornness will begin to creep up on you. The same depth of implication is found in the ancient saying that a single fallen leaf from the wutong tree is more than enough to inform the world of autumn’s presence.

The sporadic feeble chirping of cicadas is especially characteristic of autumn in the North. Due to the abundance of trees and the low altitude of dwellings in Peiping, cicadas are audible in every nook and cranny of the city. In the South, however, one cannot hear them unless in suburbs or hills. Because of their ubiquitous shrill noise, these insects in Peiping seem to be living off every household like crickets or mice.

As for autumn rains in the North, they also seem to differ from those in the South, being more appealing, more temperate.

A sudden gust of cool wind under the slaty sky, and raindrops will start pitter-pattering. Soon when the rain is over, the clouds begin gradually to roll towards the west and the sun comes out in the blue sky. Some idle townsfolk, wearing lined or unlined clothing made of thick black cloth, will come out pipe in mouth and, loitering under a tree by the end of a bridge, exchange leisurely conversation with acquaintances with a slight touch of regret at the passing of time:

“Oh, real nice and cool — ”

“Sure! Getting cooler with each autumn shower!”

Fruit trees in the North also make a wonderful sight in autumn. Take jujube trees for example. They grow everywhere — around the corner of a house, at the foot of a wall, by the side of a latrine or outside a kitchen door. It is at the height of autumn that jujubes, shaped like dates or pigeon eggs, make their appearance in a light yellowish-green amongst tiny elliptic leaves. By the time when they have turned ruddy and the leaves fallen, the northwesterly wind will begin to reign supreme and make a dusty world of the North. Only at the turn of July and August when jujubes, persimmons, grapes are 80-90 percent ripe will the North have the best of autumn — the golden days in a year.

Some literary critics say that Chinese literati, especially poets, are mostly disposed to be decadent, which accounts for predominance of Chinese works singing the praises of autumn. Well, the same is true of foreign poets, isn’t it? I haven’t read much of foreign poetry and prose, nor do I want to enumerate autumn-related poems and essays in foreign literature. But, if you browse through collected works of English, German, French or Italian poets, or various countries’ anthologies of poetry or prose, you can always come across a great many literary pieces eulogizing or lamenting autumn. Long pastoral poems or songs about the four seasons by renowned poets are mostly distinguished by beautiful moving lines on autumn. All that goes to show that all live creatures and sensitive humans alike are prone to the feeling of depth, remoteness, severity and bleakness. Not only poets, even convicts in prison, I suppose, have deep sentiments in autumn in spite of themselves. Autumn treats all humans alike, regardless of nationality, race or class. However, judging from the Chinese idiom qiushi (autumn scholar, meaning an aged scholar grieving over frustrations in his life) and the frequent selection in textbooks of Ouyang Xiu’s On the Autumn Sough and Su Dongpo’s On the Red Cliff, Chinese men of letters seem to be particularly autumn-minded. But, to know the real flavour of autumn, especially China’s autumn, one has to visit the North.

Autumn in the South also has its unique features, such as the moon-lit Ershisi Bridge in Yangzhou, the flowing sea tide at the Qiantangjiang River, the mist-shrouded Putuo Mountain and lotuses at the Lizhiwan Bay. But they all lack strong colour and lingering flavour. Southern autumn is to Northern autumn what yellow rice wine is to kaoliang wine, congee to steamed buns, perches to crabs, yellow dogs to camels.

Autumn, I mean Northern autumn, if only it could be made to last forever! I would be more than willing to keep but one-third of my life-span and have two-thirds of it bartered for the prolonged stay of the season!

《故都的秋》是郁达夫(1896—1945)的名篇,1934年8月写于北平。文章通过对北国特有风物的细腻描绘,抒发作者对故都之秋的无比眷恋之情。

注释

〔1〕 “总是好的”不宜照字面直译。现译为always has something to recommend itself,其中to have…to recommend…作“有……可取之处”解。

〔2〕 “不远千里,要从杭州赶上青岛……”译为have made light of travelling a long distance from Hangzhou to Qingdao…,其中to make light of是成语,作“对……不在乎”解。

〔3〕 “总看不饱,尝不透,赏玩不到十足”不宜逐字直译。译文without ever relishing to my heart’s content…中用relishing to my heart’s content概括原文中的“看……饱”、“尝……透”、“赏玩……”等。

〔4〕 “每年到了秋天,总要想起陶然亭的芦花……”译为the arrival of each autumn will put me in mind of Peiping’s Tao Ran Ting with its reed catkins …,其中to put one in mind of…是成语,作“使人想起……”解。译文中的Peiping’s是添加成分,以便国外读者理解句中所列各景点的所在地是北平。

〔5〕 “既觉得细腻,又觉得清闲”中的“清闲”意同“幽静”,故译quiet。

〔6〕 “可和蟋蟀耗子一样,简直像是家家户户都养在家里的家虫”译为seem to be living off every household like crickets or mice,其中to live off(=to live on)是成语,作“靠……生活”解,用以表达“养在……的家虫”。

〔7〕 “更像样”意即“更有节制”,故译为more temperate。

〔8〕 根据上下文,“微叹”是为“感怀时光的消逝”,故以释义方法译为with a slight touch of regret at the passing of time。

〔9〕 “西北风就要起来了”译为the northwesterly wind will begin to reign supreme,其中to reign supreme强调“占优势”之意。

〔10〕 “感到不能自已的深情”译为have deep sentiments … in spite of themselves,其中in spite of oneself是成语,作“不由自主地”解。

〔11〕 “秋士”是古汉语,指“士之暮年不遇者”,现译为qiushi (autumn scholar, meaning an aged scholar grieving over frustrations in his life)。

〔12〕 “欧阳子的秋声”即“欧阳修所作的《秋声赋》”,现译为Ouyang Xiu’s On the Autumn Sough。

〔13〕 《赤壁赋》为苏东坡所作,借秋游赤壁,抒发自已的人生感慨。可译为On the Red Cliff或Fu on the Red Cliff。

帕布莉卡

帕布莉卡