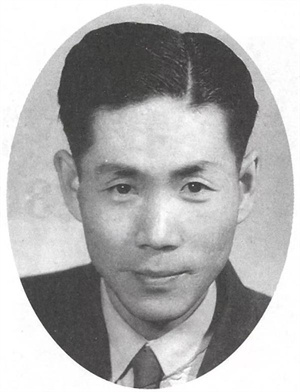

◎ 端木蕻良 Duanmu Hongliang

黎明的眼睛

◎ 端木蕻良

三月清晨,把窗子推开①,第一片阳光便飞到人们的全身②。对着阳光带进来的新鲜空气,任谁都要深吸一口,说:春天来了!

就这样,春天从窗口走近了我们。

但是,可不要忘记,不是从有房子那天起,我们就有窗子的呢!③

我们的兄弟,爱斯基摩人用冰块④建筑的房子,像个白玉的钟罩一般,是没有什么窗子的。过去的鄂伦春兄弟们住的“神仙柱”,因为没有屋顶,在屋里,到晚上可以看到头上的月亮和星光,也就无须开窗子了。

最早的人类山顶洞人走下山来,不知住过多少代,才懂得造个窝儿的时候,他们也只会模仿岩洞,把地挖个半截坑、上面再搭上个顶篷。至于窗子,就谈不上了。

房墙上开窗子是后来的事⑤。随着窗子的开凿和扩大,人类文明的曙光也随着扩大⑥。

窗子,自从它出现的那天起,它就成为阳光的眼睛,空气的港口,成了自然和社会的纽带。

随着时间流逝,层楼的加多,窗子也越来越多了。看到高层的建筑,就会惊叹窗子是房屋最鲜明的象征。没有窗子的房子,几乎也就没法把它唤作屋子了。

有谁未曾享受过开窗的喜悦呢?打开窗子,突然见到青山闯了进来,打开窗子,看到柳色的清新,小燕的飞来……

窗子开了,用不着打招呼,新的空气就会猛扑进来⑦。

当然,随之而来的,也有风沙⑧飞入屋中。还有,眼睛看不到的微尘,还有很难发觉的细菌,有的是出面拜访,有的是偷偷地混了进来……

从古到今多少诗人赞美过窗子,多少歌手歌唱过窗子,多少情人的眼睛凝望过窗子⑨……

窗子的变化⑩,是值得人们考察一番的。小小的窗子,几乎可以说,是文明的眼睛。在今后的日子里,窗子的变化会更加多种多样了。

窗子的玻璃会随着时钟,自动调和射进室内的光线⑪,窗子会随着明暗变换颜色,窗框上装有循环水,它可以为居室的主人带走很多他发觉不到的天敌,又可以送进来他需要而又不易得到的芳香和养分……

有的窗子不需开合⑫,便能做到通风透光,它还可以把你不愿听到的声音关到外边,但是悦耳的琴声,它是不会阻拦的……

打开窗子吧!现在开窗子就不光是为了迎进阳光、空气,或者远眺青山的青、新柳的绿、燕子飞来的掠影……而是迎接一个新的世纪⑬!

The Window

◎ Duanmu Hongliang

When you throw open your window on an early morning in March, you will at once be totally exposed to the sun’s first rays and, inhaling deeply of the fresh air brought in by them, exclaim, “Spring is here!”

Yes, it is through the window that spring manages to approach us.

But don’t forget that not all houses have been windowed ever since man first began to build them.

Our Eskimo brothers’ houses, built of large blocks of frozen snow and shaped like white-jade clock covers, have no windows at all. Our Oroqen⑭ brothers used to live in roofless houses with no need for windows because they could in the evening enjoy the moon and stars overhead indoors.

Man’s ancestors had been cave-dwellers before they left their mountains to settle on the plain. It was not until countless generations later that they began to build dwellings patterned after a cave — with an awning over a shallow pit in the ground. There was no window to speak of.

Making a window in the wall was a much later invention. As the popularity of windows grew, so did the civilization of man develop.

The window, ever since its birth, has been an entrance to sunlight, a port for taking in fresh air, and a tie between nature and human society.

With the passage of time and increase of tall buildings, more and more windows have appeared. Now, at the sight of a multi-storey building, one cannot help exclaiming at how the window is so symbolic of the house. Without a window, a house could hardly be called as such.

Who hasn’t experienced great delight in opening a window? The moment you open it, you will be immediately struck by imposing blue mountains, fresh green willows, little swallows flying towards you…

Open the window, and fresh air will break in upon your room.

Of course, grains of sand will simultaneously be brought in too. So will invisible dust particles and bacteria, either openly or surreptitiously…

From ancient times to the present, innumerable poets have sung their praises of the window, innumerable singers have extolled it, innumerable lovers have fixed their dreamy eyes on it…

The evolution of the window is worthy of our study. Small as it is, the window has opened man’s eyes to civilization. In the days to come, its changes will become even more manifold.

The window pane will, along with the tick-tick of the clock, automatically regulate light streaming into the room and change its own colour according to interior illumination. The window frame will be filled with circulatory water to remove things harmful to the resident without his knowledge and carry to him fragrance and nutrients which he much needs but are otherwise hard for him to get.

Some windows will ensure good ventilation and transparency without manual manipulation. They will keep out disturbing noises and let in sweet music.

Let’s open the window! Open it not just to let in sunlight and air or to get a distant view of blue mountains, fresh green willows and swallows in flight…, but, more importantly, to usher in a new century!

端木蕻良(1912—1996),辽宁省昌图县人,满族,是现代作家。他于三十年代初出现在中国文坛,曾先后主编多种刊物,并教过大学。《黎明的眼睛》是他写于1980年2月的一篇散文。文章借窗口见人类文明之过去、现在和未来,展示了窗子和人类文明的同步发展。

注释

①“把窗子推开”可译为throw open the window或open the window,但前者更切合原意。

②“第一片阳光便飞到人们的全身”未按字面直译为The first rays of the sun will hit you instantly from head to foot,现按“使你立即接触到黎明的光芒”译为You will at once be totally exposed to the sun’s first rays。

③“不是从有房子那天起,我们就有窗子的呢!”按“自从人类开始建房以来,不是所有房子都有窗子”译为not all houses have been windowed ever since man first began to build houses,其中have been windowed意同have had windows。

④“冰块”应译为blocks of frozen snow或blocks of hard snow,不能译为blocks of ice,因爱斯基摩人盖房子用的是冻结的硬雪块,不是冰块。

⑤“房墙上开窗子是后来的事”可直译为Opening a window in the wall was something that took place much later,但不如Opening a window in the wall was a much later invention(或practice)简练。

⑥“随着窗子的开凿和扩大,人类文明的曙光也随着扩大”如按字面直译将欠利落,故用意译法处理:As the popularity of windows grew, so did the civilization of man develop。

⑦“窗子开了,用不着打招呼,新的空气就会猛扑进来”译为Open the window, and fresh air will break in upon the room,其中will break in upon the room意同will rush into the room without waiting to get permission。

⑧“风沙”在此指“沙粒”,故译grains of sand。

⑨“多少情人的眼睛凝望过窗子……”译为innumerable lovers have fixed their dreamy eyes on it…,其中dreamy是译文中的增益成分,作“出神的”解,为的是更好地表达原意。

⑩“变化”在此有“演化”的意思,故译evolution。

⑪“窗子的玻璃会随着时钟,自动调和射进室内的光线……”译为The window pane will, along with the tick-tick of the clock, automatically regulate light streaming into the room…,其中用将来式will… regulate表达作者对未来的设想(以下各句也如此)。又,拟声词tick-tick是译文中的增益成分,以示时钟的变动。

⑫“不需开合”译为without manual manipulation(不需人手操作),取代without having to be opened or closed,以求简洁。

⑬“而是迎接一个新的世纪!”译为but, more importantly, to usher in a new century,其中more importantly是译文中的增益成分,用以加强语气,原文虽无其词而有其意。

⑭ One of China’s ethnic minorities inhabiting northeastern Inner Mongolia and Heilongjiang.

帕布莉卡

帕布莉卡