说起香港

◎ 萧乾

除非是研究近代史的,很少人会知道中俄战争后,从本世纪初英国即与日本结为同盟。这一特殊关系一直延续到一九四一年的“珍珠港事变”。这期间,英国老百姓自然始终坚定地站在中国一边。我先是在“七七事变”头一年就有所察觉。当时上海还有租界,而大公报馆无论在津、沪、港,都始终位于洋人管辖的地方。事变前的一年——一九三六年,《大公报》就由于我发表的陈白尘一个剧本中多处提到“×洋人”(“×”是编者打的)而三次被英、日控制的工部局[1]传到法院,最终还是由于事先打了叉叉而没坐牢。

三八年至三九年间,我在香港《大公报》编文艺副刊时,因所登的稿件而与英国新闻审查官起冲突的事,更是屡见不鲜。说是“冲突”,其实,他是主子[2]。在送审的校样上他随便打个红叉,我就只好抽掉。可临时补稿不方便[3],我就索性让版面“开天窗”,空白着。如果翻阅那一时期的香港《大公报》,天窗是不少的。有一回审查官甚至把半个版面全给枪毙了[4]。

为什么?因为中日虽在开战,英、日仍在结盟。香港殖民当局不许在它管辖的地方对日军的在华暴行进行抗议。统治者说了算,没什么道理可讲![5]

三九年秋,我应伦敦大学东方学院之邀,赴英教书。坐的是法国轮船。行至西贡,轮船被征调。其他国家的客人均可自觅旅馆,惟独几十名中国旅客,被押往集中营。幸而我在途中托人给当地总领事(我的燕京同学)送去一名片,才又改为软禁。

经过多方周折,我于十月最终来到英国港口福克斯通办理登陆手续时,官员发给我的竟是一纸“敌性外侨”的入境证。我向主管人质问,回答得简单:中、日在交战,而英、日是同盟国,因此,只能那样定性[6]。

这黑锅我一直背到一九四一年“珍珠港事变”。一天之内,我又成为“伟大盟友”了。英、日缔结的盟约,随着太平洋上的烽火自然也就烟消云散了。

对香港本身,我当然有许多美好的记忆。我在那岛上恋爱过,在浅水滩柔软的沙滩上翻滚过,我曾多次登山看夜景,尤其八六年至八七年我还以访问学人身份在沙田中文大学(世界上最美丽的大学)有过一段难忘的勾留。也正因为如此,我对香港的回归祖国,倍感欣悦。

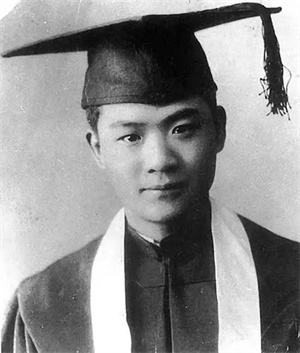

萧乾(1910—1999),北京人,著名老报人、作家、翻译家,1935年毕业于燕京大学新闻系,先后主编过天津、上海、香港等地《大公报》文艺副刊。所著《说起香港》乃一篇香港回归祖国感言,历数作者在英、日长期结盟的年代身受英国政府种种刁难与歧视。

[1]“工部局”即the Municipal Council of the International Settlement,“被英、日控制的工部局”应译为the Shanghai Municipal Council under British and Japanese control。

[2]“其实,他是主子”译为or rather with my masters,其中or rather(或rather)作“更确切地说”解。

[3]“可临时补稿不方便”意即“因临时更换稿子有困难”,可译为being hard pressed to find a replacement,其中to be hard pressed to …(或for …)作“缺少”、“找不到”解。

[4]“有一回审查官甚至把半个版面全给枪毙了”译为Once the British censor even had half a page killed,其中用to kill表达“删除”、“不予刊用”等,是国外新闻出版界常用口语,现与原文中的“枪毙”不谋而合。

[5]“没什么道理可讲!”译为There was no reasoning with them!,意同No use reasoning with them!或It was impossible to reason with them!

[6]“因此,只能那样定性”可按“因此,就是这样,没有什么可多讲的”译为So, that’s that或So, that’s it。

About Hong Kong

◎ Xiao Qian

Most people, apart from those familiar with modern history, are unaware that as early as the turn of the century (after the Sino-Russian War), Britain entered into alliance with Japan. The special relationship lasted until the outbreak of the Pearl Harbor Incident in 1941. Meanwhile, however, the British people remained firm in siding with China. It was in the year when the July 7 Incident[1] broke out that I first became aware of the said alliance between Britain and Japan. In those days, there were foreign settlements in Shanghai. And The Dagong Bao[2] had its office successively located in the foreign-controlled districts of Tianjin, Shanghai and Hong Kong. In 1936, one year before the July 7 Incident, because I had one of Chen Baichen’s[3] plays published, in which there appeared several times the expression“X foreigner”(the cross X had been added by the editor), I was summoned to court by the Shanghai Municipal Council under British and Japanese control. Finally, thanks to the cross put into the manuscript, I was exempted from imprisonment.

From 1938 to 1939, when I was in charge of editing the Art and Literature Supplement of The Dagong Bao, I often got into disputes with British censors (or rather with my masters) over manuscripts. When a British censor put in a red cross at will, all I could do was withdraw the entire manuscript. Sometimes, being hard pressed to find a replacement for it, I had to leave a blank on the page to show that something had been suppressed by censorship. Take a look at The Dagong Bao published in Hong Kong in those days, and you’ll find lots of blanks. Once the British censor even had half a page killed.

Why? Because China and Japan were at war, and Britain and Japan were allies. The Hong Kong colonial authorities prohibited any protest staged in a region under their jurisdiction against the atrocities of the Japanese troops in China. Their word was law. There was no reasoning with them!

In the autumn of 1939, I went to England to teach at the invitation of the College of Oriental Studies of the University of London. I sailed on a French steamer. When the ship arrived at Saigon, it was requisitioned and all passengers were to look for hotels for themselves except the several scores of Chinese who were escorted to concentration camps. Luckily, I was instead put under house arrest after I asked somebody to pass on my visiting card to the local Chinese consul general, who happened to be a former schoolmate of mine at Yenching University, Beijing.

After going through a lot of trouble, I finally arrived at the port of Folkestone, England. But, while going through entry formalities, the entry certificate issued to me by the British officials turned out to be one for an“enemy national residing abroad.”When I asked the official in charge for the reason why, the answer he gave was very simple,“China and Japan are at war while Britain and Japan are allies. So, that’s that!”

I remained a scapegoat until 1941 when I became a“great ally”overnight at the outbreak of the Pearl Harbor Incident. The alliance between Britain and Japan then vanished into the air with the flames of war raging over the Pacific.

As to Hong Kong, I of course cherish many beautiful memories. I had my love affair on that island, I played on the fine sands of its beaches, I many times climbed up its mountains to watch the night scenes. From 1986 to 1987, in particular, I spent a period of unforgettable days as a visiting scholar at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, New Territories, which had the most picturesque campus in the world. All that accounted for my redoubled joy over the return of Hong Kong to our motherland.

[1]The July 7 Incident (also known as the Lugouqiao Incident) of 1937 was an incident staged at Lugouqiao, Beijing on July 7, 1937, by the Japanese imperialists, which marked the beginning of an all-out war of aggression against China by Japan.

[2]The Dagong Bao(formerly known as L’impartial), a Chinese newspaper first published on June 17,1902 in Tianjin, later in Beijing on October 1, 1956 and now in Hong Kong known as The Tak Kung Pao.

[3]Chen Baichen (1908—1994), born in Huaiyin, Jiangsu Province, was a well known playwright and novelist. In the 1960s, he was vice editor-in-chief of the magazine People’s Literature.

帕布莉卡

帕布莉卡