从《老黑奴》说起[1]

◎ 萧乾

1985年5月,我去武汉参加“黄鹤楼笔会”那次,东道主湖北省文联曾邀请来自各地的作家们乘豪华的长江客轮,畅游三峡。我曾在秋天去过三峡。春日的三峡风光明媚,更加清丽可人。[2]同船的还有个外国旅游团,是由抗战时在滇缅前线同我们并肩作战过的美国名将史迪威的女儿南西率领的。船航到神女峰脚下时,我们正在甲板上举行着一次联欢会[3]。他们鼓掌一定要我们也出个节目。为了表示友好,我们几个就凑在一起(记得有宗璞、艾芜、邹荻帆、绿原和黄裳)用英语唱了一首《老黑奴》。唱得当然十分蹩脚[4]:声音既不洪亮,肯定还常走调。这是一支十分凄凉的歌曲,黑人厌倦了尘世,听到已死去的亲人的呼唤,渴望奔向另一世界[5]。所以在叠句歌里就反复唱着:我来啦,我来啦。

这样充满悲哀情调的歌,与当时甲板上的欢乐气氛,实在很不谐调。可是唱完之后,居然博得了美国旅伴们一阵热烈的掌声。我们这些平素伏案爬格子的[6]对自己这一番反串,倒也颇有些飘飘然。我们得意的不一定是因为那掌声,而是对自己感到既愉快又吃惊:这么多年,竟然还没把它忘掉!

这首歌的歌词和曲调都同出自19世纪中叶美国作曲家斯蒂芬·福斯特之手。他出生于1826年,一共只活了短短的38年。南北战争[7]打响两年后(1864),他就去世了。可惜我没读过他的传记,他肯定十分同情黑人并为他们抱不平的[8]。我熟悉好几首他编的描述黑人生活的歌曲,像《双亲在家园》(1851)。我还有幸在伦敦的一次音乐会上,听过著名黑人歌手保罗·罗伯逊唱过《老人河》。那次,他还唱了咱们的《游击队之歌》。

很奇怪,河的形象时常在黑人的歌曲中出现。像“远远地在斯旺尼河上”。也许他们在美国南方那一望无际的旱地上干活,受着白人的虐待,心里渴望有一片水。

天堂也经常在黑人歌曲中出现。处于绝境的人们就是靠这种幻想来解脱一些痛苦。

福斯特也有些歌写得轻快。像他的《苏珊娜》(1848)就描绘出一个歪戴宽沿草帽[9],无忧无虑的牛仔在追求着他心爱的姑娘。他在歌中除了抒发黑人在奴役中的痛苦之外,也亲切地描绘了他们的生活。像《我的肯塔基故乡》就富于泥土气息,真切生动地唱出了美国南方黑人的生活情景:“玉米穗成熟。牧场遍地花怒放;小鸟终日歌唱好悠扬,娃娃滚戏小农舍地板上。”不过歌曲仍是在忧伤中结束的:

莫再哭泣,姑娘,今天莫再哀伤,

我们唱一支歌,为肯塔基故乡,

为那遥远的肯塔基故乡。

当然,有些流传到中国的美国歌曲描绘的不一定都是黑人的生活。我记得有一支曲子是写铁路建筑工人的。这里也可以看到19世纪美国向西部开发时的艰苦。

同样流行于30年代的一首外国歌曲是《伏尔加船夫曲》。像咱们的四川号子一样,这里描绘的是在伏尔加河上拉纤的俄罗斯河工的苦状。他们背着纤绳,弯着腰,哎哟嗬,哎哟嗬地吆喝着,呻吟着。一把又一把地捯着,吃力地向前踏步[10]。

这些外国歌曲那时在中国那么风行,当然是因为它们歌词朴素,曲调又琅琅上口,但我认为这还不是主要的。这里既包含着中国人民对于美国黑奴以及伏尔加河纤工的深切同情,同时,也抒发了我们自己在生活中的怨艾。当时的中国,也是喘息在列强的重压之下。北京东交民巷的围墙上还有对着市民的黑洞洞的炮眼[11],上海马路还有红头阿三[12]在巡逻。正因为如此,在中国戏剧史上最早上演的外国话剧是《黑奴吁天录》(如今改译为《汤姆叔叔的小木屋》)。

歌曲的流行,往往是由于引起共鸣。

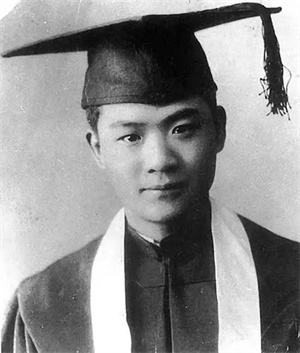

萧乾(1910—1999)原名萧炳乾,著名老报人、作家、翻译家。所著《从〈老黑奴〉说起》一文原载1992年4月6日《羊城晚报》。

[1]题目《从〈老黑奴〉说起》,斟酌文章内容,译为Old Black Joe and Other Songs,简明利落,比直译A Chat Beginning with Old Black Joe可取。

[2]“我曾在秋天去过三峡。春日的三峡风光明媚,更加清丽可人”,两句内容紧密连贯,最好合并起来译为一句:Having previously visited the autumn scene of the Three Gorges, I now found it even more picturesque and enchanting in spring,其中Having previously visited the autumn scene of the Three Gorges是Having previously visited the Three Gorges in autumn的变通。

[3]“我们正在甲板上举行着一次联欢会”译为we were in the midst of a get-together on deck,其中in the midst of意同in the middle of,两者都是成语,作“正忙于”解。又,get-together意同small social gathering,party,meeting等。

[4]“唱得当然十分蹩脚”可译为Our vocal performance, as expected, turned out lousy,其中lousy是俗语,意同poor。又,“当然”意即“意料之中”,故译为as expected,比of course确切。此句也可译为We sang very poorly as expected。

[5]“另一世界”可译为the other world,a better world,a better land等。

[6]“我们这些平素爬格子的”意即“我们这些耍笔杆子的”、“我们这些作家们”,故译为Writers by profession,As writers等。

[7]“南北战争”指“美国内战”(1861—1865),应译为the American Civil War。

[8]“他肯定十分同情黑人并为之抱不平的”译为He must have had every sympathy with Black Americans and championed justice to them,其中every sympathy意同deep sympathy;又,championed justice to them的意思是“捍卫黑人的正义”。

[9]“歪戴宽沿草帽”可译为tilting his broad-brimmed straw hat sideways或wearing his wide-brimmed straw hat askew。

[10]“一把又一把地捯着,吃力地向前踏步”译为They inch forward laboriously, pulling the line hand over hand,其中hand over hand是成语,作“双手交互使用地”解。

[11]“对着市民的黑洞洞的炮眼”译为dark portholes trained on Chinese residents,其中trained on 作“对准”、“瞄准”解。

[12]“红头阿三”为沪语,指“戴头巾的印度巡捕”,故译为turbaned Indian police。当时,上海英租界雇用的印度警察大都是头戴各色头巾的印度锡克人。

Old Black Joe and Other Songs

◎ Xiao Qian

In May 1985, I went to Wuhan to attend the Huanghelou Writers’ Forum. The Hubei Federation of Literary and Art Circles, acting as host for the event, invited us, writers from all over the country, to go on a delightful trip to the Three Gorges of the Yangtze River by luxury liner. Having previously visited the autumn scene of the Three Gorges, I now found it even more picturesque and enchanting in spring. On the same ship was an American tourist group headed by Nancy, daughter of famous US general Joseph Warren Stilwell, who served in China during World War II, fighting side by side with Chinese soldiers against Japan on the Yunnan-Burma front. When the ship arrived at the foot of Mount Goddess, we were in the midst of a get-together on deck. The American friends, clapping their hands, persistently called on us for a performance. So, to be friendly, we, including Zong Pu, Ai Wu, Zou Difan, Lu Yuan and Huang Chang, if I remember correctly, grouped together to sing in English the American folk song Old Black Joe. Our vocal performance, as expected, turned out lousy. We sang in a low and unclear voice, and evidently out of tune again and again. It was a very sad and plaintive song. The said Black Joe, being sick and tired of the mortal world, longs to go to a better world on hearing the gentle voice of his departed folks calling,“Old Black Joe!”Hence the refrain,“I’m coming, I’m coming!”

The song, full of pathos, was completely out of harmony with the joyous atmosphere of the moment on deck. Nevertheless, we won the warm applause of our American fellow travelers. Writers by profession, we felt quite self-satisfied after acting a role other than our own. But we felt pleased with ourselves not because of the warm applause, but because we were surprised to find ourselves still remembering the words of the song after so many years.

Both the words and tune of the song were written by Stephen C. Foster, famous American composer of the 19th century. Born in 1826, he died in 1864, two years after the outbreak of the American Civil War, ending a short life of only 38. Much to my regret, I haven’t read any of his biographies yet. He must have had every sympathy with Black Americans and championed justice to them. I’m familiar with quite a few songs of his composition describing the sad plight of Blacks, such as Old Folks at Home (1851). I was happy to listen to famous Black singer Paul Robeson sing Old Man River at a concert in London. He then also sang our Song of Guerillas.

Strangely, Black people often sing of rivers in their songs, as witness“Way down upon the Swanee River, far, far away”in Old Folks at Home. It is perhaps because they were dying for water while toiling under White tyranny on the boundless stretch of arid land in the southern states.

Likewise, heaven often appears in their songs. It is because people in a hopeless situation often indulge in fantasies to free themselves from innermost sufferings.

Some of Foster’s songs are nevertheless very lively. Take Oh! Susanna (1848) for example. It describes how a care-free cowboy, tilting his broadbrimmed straw hat sideways, is paying court to a girl he loves. It depicts not only the misery of the enslaved Blacks, but also their way of life. My Old Kentucky Home, for example, is a song full of local color. See the following genuine and vivid picture it gives of the life of the Blacks in the southern states:“The corn top’s ripe and the meadow’s in the bloom. While the birds make music all the day, the young folks roll on the little cabin floor.”But the song still ends up with grief:

Weep no more, my lady, oh! Weep no more today!

We will sing one song for the old Kentucky Home,

For the old Kentucky Home, far away.

Of course, not all American songs prevalent in China are about the life of Black people. One of them, I remember, is about American railway workers, showing the great hardship they suffered during the 19th-century westward development of the country.

Another foreign song popular in China during the thirties was The Song of the Volga Boatmen. Like the Sichuan labor chant, it describes the misery of Russian boat-trackers along the Volga River. They bend their shoulders to the tow-line, chanting in a loud voice,“Yo heave oh! Yo heave oh!”They inch forward laboriously, pulling the line hand over hand.

The erstwhile popularity of these songs in China was no doubt due to their simple and readable words. But, I think, that is not the main cause. In fact, it had much to do with the deep sympathy of the Chinese people for Black Americans and Volga boat-trackers. Meanwhile, it also reflect our own feeling of resentment against foreign aggressors. In those days, dark portholes trained on Chinese residents were still lurking on top of the walls surrounding the Legation Quarter in Beijing[1]. And turbaned Indian policemen[2] were patrolling the streets of Shanghai. That also accounts for why Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the first foreign play ever staged in China.

Songs often owe their popularity to the sympathetic response of the public.

[1]The district in Beijing where legations of big powers were located between 1861 and 1959.

[2]Referring to turbaned Sikhs hired by the Municipal Council of the then International Settlement in Shanghai to police the streets.

帕布莉卡

帕布莉卡